It’s 20 years later and I still don’t have the words. I don’t think I ever will. I spend a lot of time thinking about September 10th, 2001: the last day I could watch a low-flying plane without fear.

I was 13, and, as everyone likes to say, everything changed. These are some of the strongest throughlines in my mind, after living with the legacy of 9/11 for a generation.

- I don’t go downtown if I can’t help it. Seeing tourists with their little gift baggies from the 9/11 Memorial, or asking me for directions, fills me with inchoate rage. Fuck you and your baggies. Our trauma isn’t your tourist attraction. I can’t walk by the fountain without sobbing. A few weeks ago, I realized that the Oculus, pretty much the only post-9/11 to the city that I actually like, is partially built on one of the towers’ foundations. I wanted to throw up all over the pristine white marble that covers the station.

- In 2011, somebody announced that they were building a supertower in Midtown that would be taller than the Empire State Building, and maybe block it when viewing the island from New Jersey. My New Yorker friends and I were indignant, and our other friends didn’t get it. “Oh,” one of them remarked. “New Yorkers are very protective of their skyline.”

- I grew up on the Upper East Side and went to private school. Who sends their kids to private schools? People who work in finance. It’s statistically improbable, but none of the families in my school lost people that day. But a lot of people’s parents lost friends. I didn’t know anybody who wasn’t somehow impacted. My mom had recently started working in the World Financial Center and I couldn’t remember how close that complex was to the Twin Towers. My sister and I were among the last students to get picked up in our grade, and we spent what felt like hours worrying if she was okay. Turns out, she had taken the day off for a PTA meeting and though we would rather be with our friends. I only know realize she needed time to completely lose her fucking shit before coming to get us. She had coworkers who were looking out the window when it happened, They didn’t stay too long after that.

- I remember watching the surveillance state (that we have now privatized through social media and Internet ad tracking) balloon. For months after the attacks, I would stare out my window watching trios of “traffic officers” patrol the neighborhood. You could reliably look down at first avenue from my twelfth-story window and watch fleets of black and silver vans make loops around the island. Sure, SUVs were popular back then. But did they always travel in groups with 4 other vans of the same make and color? I now know that this is a symptom of PTSD called hypervigilance.

- Most chillingly, I remember the moment I realized that the unmarked 18-wheelers that interspersed the vans were refrigerator trucks transporting human remains from ground zero. I don’t have any information to actually confirm this, but what else could it be? They were literally all the same. I don’t see them anymore. At least, I didn’t until spring 2020. Now there’s an essay that someone else is going to write.

This grief is private and it’s difficult, especially because I was not directly impacted the way so many other people were. You can miss me with the thinkpieces that have been proliferating this week and will culminate tomorrow. I’m going to be playing softball. In the evening, my dad got us tickets for the Yankees/Mets subway series, and of course there’s going to be a ceremony. And, as much as my opinions on police officers have absolutely curdled, you bet I’m going to cry like a fucking baby in the nosebleeds at Citifield.

So Neil Nathan’s song “The Guardrail” caught me by surprise. I genuinely don’t care to process this event by reading about other people’s experiences, and you’d be forgiven if you skipped mine. But Nathan’s sunny power pop evokes September 10th. As the story of his lost friend unfolds, you’ll find yourself going through the same thing we all did 20 years ago, even if you weren’t there: the slow dawning of tragedy, the unfolding of grief, and the ambivalence of carrying on — because what else are you going to do? Below, Nathan tells us about “The Guardrail” and his memories of Fred Gabler.

Explain the title of the song.

The song is called “The Guardrail” after a place across the street from a friend’s house where all of us used to hang out and party when we were teens. I use it as a symbol for guarding our innocence, which in many ways we lost on 9/11, when our close friend passed away in the North Tower.

Does your album have an overarching theme?

The song explores the historical significance of that fateful day, the personal loss felt by so many, while reminding us of our collective responsibility in remembrance. It was such a traumatic experience. I recall visiting hospitals throughout Manhattan to see if my friend was on any admittance lists. All of us gathered at his apartment, watching CNN for any glimmer of hope, hoping he was somehow alive in the rubble. My friend was a wonderful man with a razor sharp wit and sardonic sense of humor. He was very present mentally, an in-the-moment type of guy, so it was especially difficult to process him just not being with us anymore. I wrote and sang a song for him at his funeral entitled “Freddy’s Song.” It was a way for me to grieve and attempt to express the loss I was feeling in a way that might be helpful for others too.

Some years on the anniversary of 9/11, it would just hit me, the loss of such a vibrant, smart, warm man, a great friend, husband, brother, son. And I’d just break down crying.

Last year it struck me how long it’s been since all of this happened and “The Guardrail” just poured out of me. Something about the shared trauma of the pandemic and the time to sit with your own thoughts and emotions must have fed into it too.

It was extremely difficult recording the vocals for this song and then listening to it over and over again during the mixing process with co-producer Thales Posella. It was like repeatedly ripping open an old wound. But it was very therapeutic as well. Thales had recently lost a close friend and was very sympathetic and open. The perfect person to collaborate with on the song.

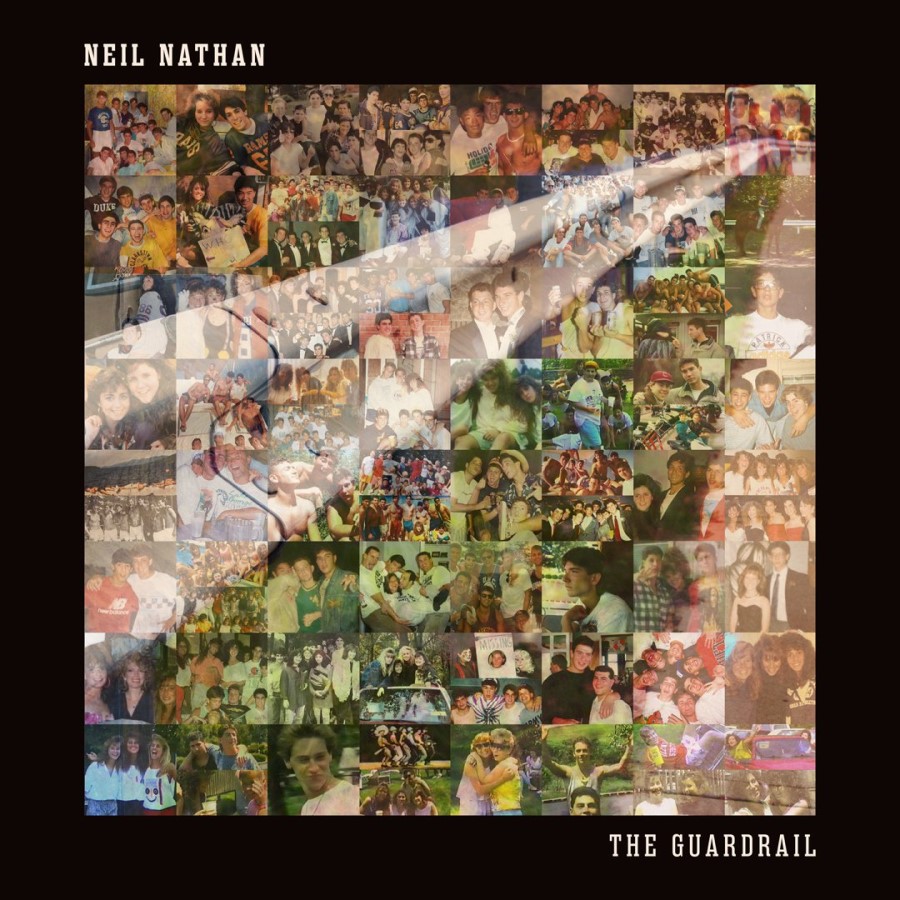

I reached out to Fred’s high school, college and summer camp friends and asked them for any photos from our glory days they might like to share for a collage album cover overlaying “The Guardrail,” and the response was incredible. There wasn’t space for them all. It felt like a kind of healing group therapy, everyone was so excited to share their memories in celebration of the love we had and still have for one another. It’s a very special group. Not many folks are still so close with so many friends from high school, college, and summer camp. Despite life taking us in so many different directions, we are truly blessed to continue to have such a wonderful and supportive peer group. A family, really.

How are you using your platform to support marginalized people?

The Fred Gabler Helping Hand Camp Fund provides financial assistance to camps and programs that allow children from underserved communities to experience the camaraderie, independence and joy that Fred and many of the Fund’s supporters were fortunate enough to partake in as children and young adults.

What’s the best way a fan can support you?

Donate to the Fred Gabler Helping Hand Camp Fund.

What are some other memories you have of life in New York after 9/11?

I remember walking on the Upper West Side to the grocery store in the days following 9/11 and the firemen and other first responders walking on the street, returning from Ground Zero. Everyone stopped and applauded them. It gave me the chills, it was so powerful. There was something very special about NYC’s response to the tragedy, a real coming together. I wish there was a way to bottle that type of community spirit in America which didn’t require a disaster to precede it.