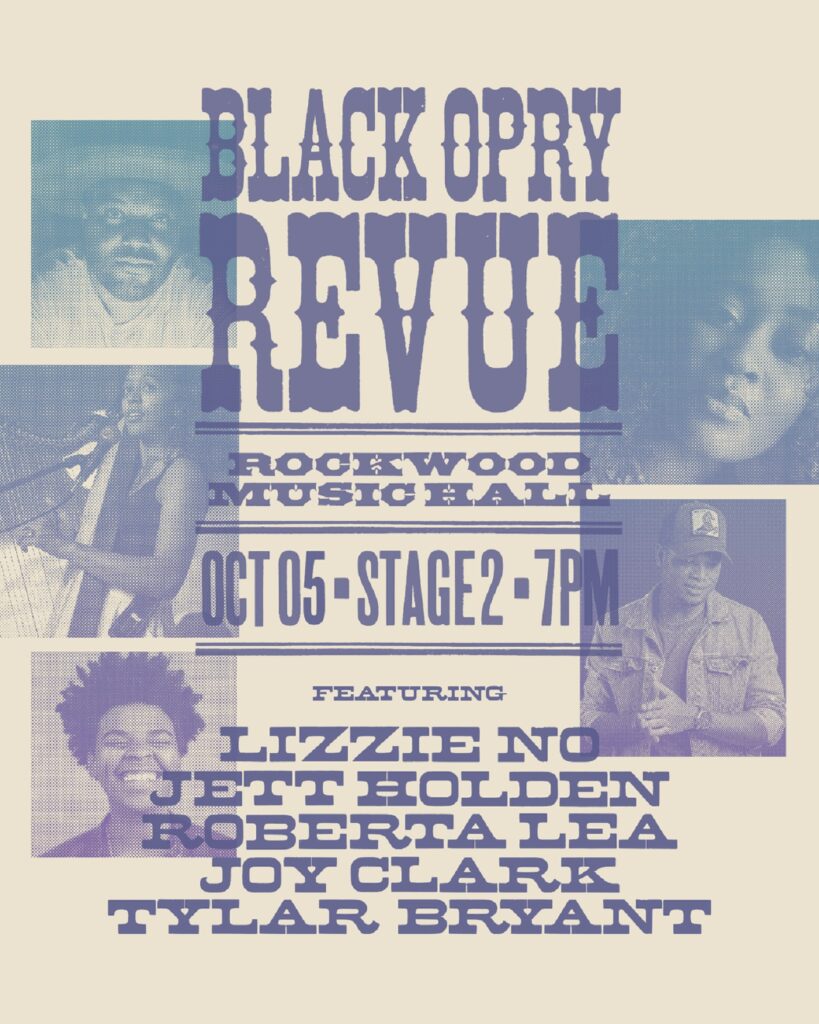

Two nights ago, the country music world shifted. Like most tectonic movements, we may not see it for a while. But with the Black Opry‘s first-ever Revue at New York City’s Rockwood Music Hall, Holly G has gathered a few of the rising stars in the country music firmament. Holly and others, like Rissie Palmer’s Color Me Country radio show and artist development grant, and the Rainey Day Fund supporting Americana artists, have worked tirelessly to advocate for Black artists in country and roots music — music, that, after all, Black artists created but rarely get credit for.

Thanks to the pandemic, the organizing that I’ve seen has mostly been online or in Nashville. With Tuesday’s concert, the Black Opry Revue is bringing country music by Black artists to the people — and giving us the opportunity to bask in these artists’ excellence.

Tuesday’s show featured Roberta Lea, Jett Holden, Lizzie No, Tylar Bryant, and Joy Clark — plus a surprise appearance by one of my favorite artists in New York, Ganessa James. The five artists performed int he round, at times joining each other with improvised harmonies and guitar accompaniment from accomplished lead guitarist Clark. The diversity of the artists represented everything I love about country music.

Roberta Lea started each round off with songs bubbling with joy, love and humor: songs that I could easily imagine with a lush pop country backing. Holden’s piercing songwriting, ranging from topics such as coming out in the church and a dear friend’s suicide, is second only to his commanding voice. Lizzie No, alternating between a gorgeous portable harp (does it have a name?) and acoustic guitar, told stories of social anxiety (wryly humorous) and experiencing racism through memories of visiting her grandmother in North Carolina. Bryant has a radio-ready voice that is smooth as bourbon, an equal match to his songwriting capability: Bryant brought the house down with his easygoing party songs as much as he did with a song about the loss of his brother — also to suicide. Clark rounded out each set with exquisite guitar work and earnest songs reminding us all of the value of taking our time and enjoying what’s in front of us. The quintet concluded the night with a powerful rendition of Black country role model Tracy Chapman’s “Fast Car,” a goosebump-raising experience that will stay with me as one of my favorite live music moments ever.

It is important to note that the night emphasized the Black country community’s intersections with the queer country community. In fact, I saw many local queer country artists and friends in the audience last night. I met Holly through working on Country Queer, and I featured Holden in mind and Terry Blade’s Juneteenth Pride podcast this past June. We are all working towards the same goal: forcing country music to accept everyone into the big circle in the center of the stage.

We also cannot pretend that things are better than they were: just last week, Paste Magazine published a disgraceful article suggesting that Black Americana musicians are over-hyped and should be relegated to a separate category of the genre. Jake Blount published a blistering response in the same magazine, though, like Jake, I question why Himes’ piece was ever run in the first place.

There’s no exaggerating the power of this moment: by drawing a crowd to a country music show outside of Nashville, the Revue has cemented itself in a legacy of self-organized movements and concert series like the Black Country Music Association in the ’90s, and reiterating what the BCMAs asserted: there is a hunger for country music by Black people, for Black people.